($define! $lambda

($vau (formals . body) env

(wrap (eval (list* $vau formals #ignore body)

env))))Through the power of fexprs, Kernel needs only three built-in operators (define, vau, and if) as well as some built-in functions. This is vastly simpler than any definition of Scheme! Scheme built-ins such as lambda, set! (!), define-syntax and others fall directly out of fexprs, for free, radically simplifying the implementation. But I'm rambling.Sunday, July 31, 2011

The meaning of forms in Lisp and Kernel

There are so many nice things to be learned from Lisp - and Kernel.

Take this:

But Lisp is never content with a form alone: it always wants to evaluate the form, determine its meaning.

For instance, when you input a symbol form, Lisp will not just return the symbol object - it will return the value of the variable binding referenced by the symbol - which is the symbol's meaning, per Lisp's rules of form evaluation.

No wonder then that one of the central features of Lisp is quotation - telling Lisp not to determine the meaning of a form presented to it, but rather give us the form itself.

So what's a form? A form is "any object meant to be evaluated", in other words, we may treat any object as a form, as something to evaluate, as something to determine the meaning of.

Lisp's evaluation rules do not prescribe in any way that forms are bound to text-based representations - a form is any first-class object meant to be evaluated. (And in fact, Racket, a leading Lisp implementation already supports images as forms.)

So Lisp is chiefly concerned with determining the meaning of forms read from the user.

Macros then allow us to extend the variety of forms recognized by a Lisp, beyond the ways that mere function calls can.

Where in a function call the meaning of every operand is established automatically before the function is actually called, macros have total freedom in evaluating - determining the meaning of - operands, or not evaluating them at all (as a short-circuiting AND operator may do, for example).

But Common Lisp and Scheme macros, by their preprocessing nature (a macro call works at a time conceptually different from runtime, translating source expressions to other expressions, to be evaluated at a later time), cannot be used in a first-class fashion. For example, it is not possible to apply the AND macro to a list of dynamically computed values (without resorting to EVAL), like we could with a function.

In a sense, macros of the preprocessing kind restrict our ability of determining the meaning of forms: With preprocessing macros, we may only determine the meaning of forms available at preprocessing time.

This where Kernel's fexprs come in. Fexprs drop the requirement of macros to be expandable in a separate preprocessing step. Thus, we may apply the AND fexpr to a list of dynamically computed operands, for example.

But fexprs go beyond being merely a more convenient replacement for macros. As John Shutt shows, a new lexically-scoped formulation of fexprs - as presented in Kernel - is even more fundamental to Lisp than lambda. In Kernel, lambda is defined in terms of vau, the ultimate abstraction:

In essence, fexprs liberate Lisp's ability to determine the meaning of forms.

It's getting midnight (on a Sunday!), so I can't do fexprs or my excitement about them justice. But I hope this post has made you think about forms and their meanings, and to check out Kernel and share the excitement about the brave new Lisp world of fexprs.

Some history

Reading the interesting Portable and high-level access to the stack with Continuation Marks, I found the following quote about procedure calls (my emphasis):

This [not properly tail-calling] behavior of the SECD machine, and more broadly of many compilers and evaluators, is principally a consequence of the early evolution of computers and computer languages; procedure calls, and particularly recursive procedure calls, were added to many computer languages long after constructs like branches, jumps, and assignment. They were thought to be expensive, inefficient, and esoteric.Guy Steele outlined this history and disrupted the canard of expensive procedure calls, showing how inefficient procedure call mechanisms could be replaced with simple “JUMP” instructions, making the space complexity of recursive procedures equivalent to that of any other looping construct.

Then it gets highly ironic, with a quote by Alan Kay:

Though OOP came from many motivations, two were central. ... [T]he small scale one was to find a more flexible version of assignment, and then to try to eliminate it altogether.

Saturday, July 30, 2011

Some nice paperz on delimited continuations and first-class macros

My current obsessions are delimited continuations (see my intro post) and first-class macros (fexprs). Here are some nice papers related to these topics:

Three Implementation Models for Scheme is the dissertation of Kent Dybvig (of Chez Scheme fame). It contains a very nice abstract machine for (learning about) implementing a Scheme with first-class continuations. I'm currently trying to grok and implement this model, and then extend it to delimited continuations.

A Monadic Framework for Delimited Continuations contains probably the most succinct description of delimited continuations (on page 3), along with a typically hair-raising example of their use.

Adding Delimited and Composable Control to a Production Programming Environment. One of the authors is Matthew Flatt, so you know what to expect - a tour de force. The paper is about how Racket implements delimited control and integrates it with all the other features of Racket (dynamic-wind, exceptions, ...). Apropos, compared to Racket, Common Lisp is a lightweight language.

Fexprs as the basis of Lisp function application or $vau: the ultimate abstraction and the Revised-1 Report on the Kernel Programming Language. These two are probably the two papers I would take to the desert island at the moment. I'm only a long-time apprentice of programming languages, but I know genius when I see it.

Three Implementation Models for Scheme is the dissertation of Kent Dybvig (of Chez Scheme fame). It contains a very nice abstract machine for (learning about) implementing a Scheme with first-class continuations. I'm currently trying to grok and implement this model, and then extend it to delimited continuations.

A Monadic Framework for Delimited Continuations contains probably the most succinct description of delimited continuations (on page 3), along with a typically hair-raising example of their use.

Adding Delimited and Composable Control to a Production Programming Environment. One of the authors is Matthew Flatt, so you know what to expect - a tour de force. The paper is about how Racket implements delimited control and integrates it with all the other features of Racket (dynamic-wind, exceptions, ...). Apropos, compared to Racket, Common Lisp is a lightweight language.

Subcontinuations. This is an early paper on delimited continuations. It also describes control filters, a low level facility on top of which dynamic-wind can be implemented. Control filters are also mentioned - in passing - as a nice tool in the Racket paper (above).

If you know of any related nice papers, let me know!

On Twitter, Paul Snively mentioned Oleg's paper Delimited Control in OCaml, Abstractly and Concretely, but probably only because he's mentioned in the Acknowlegdements - kidding! It's a great paper, and I'm studying it too, but unfortunately it's not really applicable to implementing delimited control in JavaScript, which is what I'm trying to do.

Thursday, July 28, 2011

Everything you always wanted to know about JavaScript...

...but were afraid to ask Brendan Eich. (the whole thread, starting with this post)

Thursday, July 21, 2011

On the absence of EVAL in ClojureScript

[I got bored with the original text of this post. In short: the authors of ClojureScript have taken the pragmatic approach of reusing Clojure-on-the-JVM to generate JavaScript. This means there can be no EVAL in ClojureScript. I think that's sad because Lisp is one of the finest application extension languages, and without EVAL you can't do a really extensible app. Apparently, the ClojureScript authors view the browser-side as something of an adjunct to server apps. In my view, all the action of the future will be in the browser, and not on the server.]

Thursday, July 14, 2011

Frankenprogramming

David Barbour throws down the gauntlet to John Shutt in an already interesting and entertaining ("about as coherent as a 90 day weather forecast") LtU thread:

Previously, regarding fexprs: John Shutt's blog

John Shutt would like to break the chains of semantics, e.g. using fexprs to reach under-the-hood to wrangle and mutate the vital organs of a previously meaningful subprogram. Such a technique is workable, but I believe it leads to monolithic, tightly coupled applications that are not harmonious with nature. I have just now found a portmanteau that properly conveys my opinion of the subject: frankenprogramming.I'm looking forward to John's reply. In the meantime, I have to say that I like to view this in a more relaxed way. As Ehud Lamm said:

Strict abstraction boundaries are too limiting in practice. The good news is that one man's abstraction breaking is another's language feature.

Sunday, July 10, 2011

Atwood's Law

Any application that can be written in JavaScript, will eventually be written in JavaScript.

(source; also: Duke's Law)

Friday, July 8, 2011

it is nice to have the power of all that useful but obsolete software out there

Subject: Re: Switching tasks and context

∂08-Jul-81 0232 Nowicki at PARC-MAXC Re: Switching tasks and context

Date: 6 Jul 1981 10:32 PDT

From: Nowicki at PARC-MAXC

In-reply-to: JWALKER's message of Wednesday, 1 July 1981 11:52-EDT

To: JWALKER at BBNA

cc: WorkS at AI

∂08-Jul-81 0232 Nowicki at PARC-MAXC Re: Switching tasks and context

Date: 6 Jul 1981 10:32 PDT

From: Nowicki at PARC-MAXC

In-reply-to: JWALKER's message of Wednesday, 1 July 1981 11:52-EDT

To: JWALKER at BBNA

cc: WorkS at AI

The important thing is that such a tool WORKS, and I find incredibly useful. The virtual terminal uses ANSI standard escape sequences, so we can use all the tools that have been around for a long time (like the SAIL Display Service, Emacs under TOPS-20 or Unix, etc.) with NO modifications. We are planning to use this to develop a more integrated system, but it is nice to have the power of all that useful but obsolete software out there.

(via Chris, who's scouring Unix history for us)

(via Chris, who's scouring Unix history for us)

Wednesday, June 29, 2011

PL nerds: learn cryptography instead

I've never studied cryptography. So when the paper Tahoe – The Least-Authority Filesystem fell in my lap, I was perplexed.

Using just two primitives, secret-key and public-key cryptography, they build an amazing solution to information storage. (Try to understand the two main diagrams in the paper. It's not hard, and it's amazing.)

Before encountering Tahoe-LAFS, cryptography was just a way to keep stuff secret to me. But cryptography also provides us with tools to design programs that wouldn't be possible otherwise.

Monday, June 27, 2011

State of Code interview

Zef Hemel has interviewed me for his weblog, State of Code: Lisp: The Programmable Programming Language. I don't feel qualified to be the "Lisp guy", but as you know, I never leave out an opportunity to blather about PLs.

Wednesday, June 22, 2011

John Shutt's blog

John Shutt now has a blog: Structural insight.

John is pushing the envelope of Lisp with his Kernel programming language, a "dialect of Lisp in which everything is a first-class object". And when he says everything, he means it.

Not content with just first-class functions and continuations, John also wants first-class environments and first-class macros. Some fun LtU discussions in which John participated come to mind:

Thursday, June 16, 2011

David Barbour's soft realtime model

David Barbour is to me one of the most important thinkers on distributed programming languages and systems.

Previously: Why are objects so unintuitive

He frequently posts on LtU and on Ward's wiki.

(And he now has a blog!)

In this LtU post he describes a very interesting soft realtime programming model, reminiscent of Croquet/TeaTime:

I'm also using vat semantics inspired from E for my Reactive Demand Programming model, with great success.

I'm using a temporal vat model, which has a lot of nice properties. In my model:

- Each vat has a logical time (

getTime).- Vats may schedule events for future times (

atTime, atTPlus).- Multiple events can be scheduled within an instant (

eventually).- Vats are loosely synchronized. Each vat sets a 'maximum drift' from the lead vat.

- No vat advances past a shared clock time (typically, wall-clock). This allows for soft real-time programming.

This model is designed for scalable, soft real-time programming. The constraints on vat progress give me an implicit real-time scheduler (albeit, without hard guarantees), while allowing a little drift between threads (e.g. 10 milliseconds) can achieve me an acceptable level of parallelism on a multi-core machine.

Further, timing between vats can be deterministic if we introduce explicit delays based on the maximum drift (i.e. send a message of the form '

doSomething `atTime` T' where T is the sum of getTime and getMaxDrift.

Previously: Why are objects so unintuitive

Sunday, June 12, 2011

Everything in JavaScript, JavaScript in Everything

We can now run Linux, LLVM bitcode, and a lot of other languages in JavaScript.

And we can run JavaScript in everything - browsers, servers, toasters, Lisp.

Like IP in networking, JavaScript is becoming the waist in the hourglass.

I don't know what it means yet, but it sure is exciting.

Friday, June 10, 2011

No No No No

// Note: The following is all standard-conforming C++, this is not a hypothetical language extension.

Multi-Dimensional Analog Literals

assert( top( o-------o

|L \

| L \

| o-------o

| ! !

! ! !

o | !

L | !

L| !

o-------o ) == ( o-------o

| !

! !

o-------o ) );

Multi-Dimensional Analog Literals

Tuesday, June 7, 2011

WADLER'S LAW OF LANGUAGE DESIGN

In any language design, the total time spent discussing(source, via Debasish Ghosh)

a feature in this list is proportional to two raised to

the power of its position.

0. Semantics

1. Syntax

2. Lexical syntax

3. Lexical syntax of comments

(That is, twice as much time is spent discussing syntax

than semantics, twice as much time is spent discussing

lexical syntax than syntax, and twice as much time is

spent discussing syntax of comments than lexical syntax.)

Saturday, May 28, 2011

Extreme software

Some programs are very successful with taking a paradigm to an extreme.

Emacs tries to represent every user interface as text. Even video editing.

Plan 9 tries to use filesystem trees as APIs for all applications and OS services.

It's interesting to abstract insights gained from extreme programs, and modify them.

We can ask: if Emacs is successful using plain text as user interface, what if we use hypertext?

Or: if Plan 9 is successful in using filesystem trees as APIs, what if we use activity streams?

Ouch

Few companies that installed computers to reduce the employment of clerks have realized their expectations.... They now need more, and more expensive clerks even though they call them "operators" or "programmers."— Peter F. Drucker

Wednesday, May 18, 2011

TermKit

I happen to think that pushing beyond plain text is one of the most important tasks for programmers today, or as Conor McBride put it:

The real modern question for programmers is what we can do, given that we actually have computers. Editors as flexible paper won't cut it.

So of course I like TermKit:

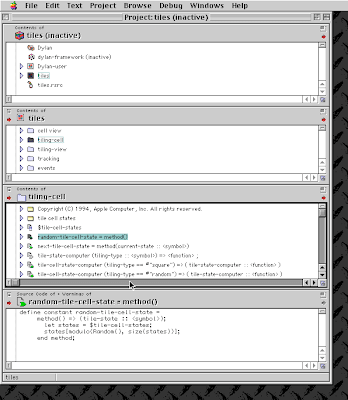

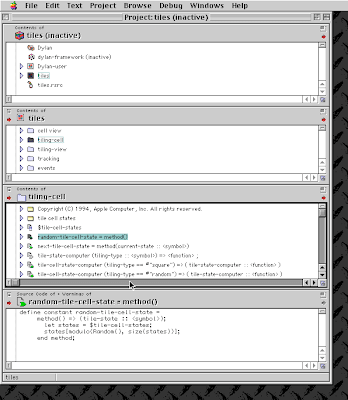

It brings back memories of Apple Dylan:

It's simple: replace plain text files with collections, and lines with objects, and you get Good Things for free!

For example: Scott McKay describes the DEUCE editor:

The editor for FunO's Dylan product -- Deuce -- is the next generation of Zwei in many ways. It has first class polymorphic lines, first class BPs [buffer pointers], and introduces the idea first class "source containers" and "source sections". A buffer is then dynamically composed of "section nodes". This extra generality costs in space (it takes about 2 bytes of storage for every byte in a source file, whereas gnuemacs and the LW editor takes about 1 byte), and it costs a little in performance, but in return it's much easier to build some cool features:

- Multiple fonts and colors fall right out (it took me about 1 day to get this working, and most of the work for fonts was because FunO Dylan doesn't have built-in support for "rich characters", so I had to roll my own).

- Graphics display falls right out (e.g., the display of a buffer can show lines that separate sections, and there is a column of icons that show where breakpoints are set, where there are compiler warnings, etc. Doing both these things took less than 1 day, but a comparable feature in Zwei took a week. I wonder how long it took to do the icons in Lucid's C/C++ environment, whose name I can't recall.)

- "Composite buffers" (buffers built by generating functions such as "callers of 'foo'" or "subclasses of 'window') fall right out of this design, and again, it took less than a day to do this. It took a very talented hacker more than a month to build a comparable (but non-extensible) version in Zwei for an in-house VC system, and it never really worked right.

Of course, the Deuce design was driven by knowing about the sorts of things that gnuemacs and Zwei didn't get right (*). It's so much easier to stand on other people shoulders...

Saturday, May 14, 2011

Secret toplevel

A somewhat arcane aspect of hygienic macro systems is the notion that macro-introduced toplevel identifiers are secret.

(#' is EdgeLisp's code quotation operator.)

An example of this in EdgeLisp:

The macro FOO expands to code that defines a variable X using DEFVAR, and prints its value:

(defmacro foo () #'(progn (defvar x 1) (print x)))

(#' is EdgeLisp's code quotation operator.)

Using the macro has the expected effect:

(foo)

1

But X isn't actually a global variable now:

x

; Condition: The variable x is unbound.

; Restarts:

; 1: #[handler [use-value]]

; 2: #[handler [retry-repl-request]]

; 3: #[handler [abort]]

The name X only makes sense inside the expansion of (foo). Outside, it gets transparently renamed by the hygienic macro system.

(In EdgeLisp, a UUID is attached as color (or hygiene context) to the identifier.)

Why the secrecy of toplevel variables? Well, it's simply an extension of the notion that identifiers that introduce new variable bindings (such as those in a LET) need to be treated specially to prevent unhygienic name clashes between macro- and user-written code. This secrecy completely frees macro writers from having to care about the identifiers they choose.

(Discussion of this topic on the R7RS list: Are generated toplevel definitions secret?)

Wednesday, May 11, 2011

The why of macros

Good analysis by Vladimir Sedach:

The entire point of programming is automation. The question that immediately comes to mind after you learn this fact is - why not program a computer to program itself? Macros are a simple mechanism for generating code, in other words, automating programming. [...]

This is also the reason why functional programming languages ignore macros. The people behind them are not interested in programming automation. [Milner] created ML to help automate proofs. The Haskell gang is primarily interested in advancing applied type theory. [...]

Adding macros to ML will have no impact on its usefulness for building theorem provers. You can't make APL or Matlab better languages for working with arrays by adding macros. But as soon as you need to express new domain concepts in a language that does not natively support them, macros become essential to maintaining good, concise code. This IMO is the largest missing piece in most projects based around domain-driven design.

Tuesday, May 10, 2011

Hygiene in EdgeLisp

EdgeLisp is chugging along nicely. I'll soon do a proper release.

I just implemented a variant of SRFI 72, that is a hygienic defmacro. (I wrote two articles about SRFI 72: part 1 and part 2).

(defmacro swap (x y)

#`(let ((tmp ,x))

(setq ,x ,y)

(setq ,y tmp)))

nil

(defvar x 1)

1

(defvar tmp 2)

2

(swap x tmp)

1

x

2

tmp

1

(swap tmp x)

1

x

1

tmp

2

Sunday, May 8, 2011

Compiling, linking, and loading in EdgeLisp

EdgeLisp now has first-class object files (called FASL, for Fast-Loadable) and a primitive linker:

Let's compile a FASL from a piece of code:

(defvar fasl (compile #'(print "foo")))

#[fasl [{"execute":"((typeof _lisp_function_print !== \"undefined\" ? _lisp_function_print : lisp_undefined_identifier(\"print\", \"function\", undefined))(null, \"foo\"))"}]]

(Note that EdgeLisp uses #' and #` for code quotation.)

The FASL contains the compiled JavaScript code of the expression (print "foo").

We can load that FASL, which prints foo.

(load fasl)

foo

nil

Let's create a second FASL:

(defvar fasl-2 (compile #'(+ 1 2)))

#[fasl [{"execute":"((typeof _lisp_function_P !== \"undefined\" ? _lisp_function_P : lisp_undefined_identifier(\"+\", \"function\", undefined))(null, (lisp_number(\"+1\")), (lisp_number(\"+2\"))))"}]]

(load fasl-2)

3

Using link we can concatenate the FASLs, combining their effects:

(defvar linked-fasl (link fasl fasl-2))

(load linked-fasl)

foo

3

(compile #'(defmacro foo () #'bar))

#[fasl [

execute:

(typeof _lisp_variable_nil !== "undefined" ? _lisp_variable_nil : lisp_undefined_identifier("nil", "variable", undefined))

compile:

Let's compile a FASL from a piece of code:

(defvar fasl (compile #'(print "foo")))

#[fasl [{"execute":"((typeof _lisp_function_print !== \"undefined\" ? _lisp_function_print : lisp_undefined_identifier(\"print\", \"function\", undefined))(null, \"foo\"))"}]]

(Note that EdgeLisp uses #' and #` for code quotation.)

The FASL contains the compiled JavaScript code of the expression (print "foo").

We can load that FASL, which prints foo.

(load fasl)

foo

nil

Let's create a second FASL:

(defvar fasl-2 (compile #'(+ 1 2)))

#[fasl [{"execute":"((typeof _lisp_function_P !== \"undefined\" ? _lisp_function_P : lisp_undefined_identifier(\"+\", \"function\", undefined))(null, (lisp_number(\"+1\")), (lisp_number(\"+2\"))))"}]]

(load fasl-2)

3

Using link we can concatenate the FASLs, combining their effects:

(defvar linked-fasl (link fasl fasl-2))

(load linked-fasl)

foo

3

Compile-time effects

Fasls keep separate the runtime and the compile-time effects of code.

For example, a macro definition returns nil at runtime, and does its work at compile-time (edited for readability):

#[fasl [

execute:

(typeof _lisp_variable_nil !== "undefined" ? _lisp_variable_nil : lisp_undefined_identifier("nil", "variable", undefined))

compile:

((typeof _lisp_function_Nset_macro_function !== "undefined" ? _lisp_function_Nset_macro_function : lisp_undefined_identifier("%set-macro-function", "function", undefined))(null, "foo", (function(_key_, _lisp_variable_NNform){ lisp_arity_min_max(arguments.length, 2, 2); return (((typeof _lisp_function_Ncompound_apply !== "undefined" ? _lisp_function_Ncompound_apply : lisp_undefined_identifier("%compound-apply", "function", undefined))(null, (function(_key_){ lisp_arity_min_max(arguments.length, 1, 1); return (((new Lisp_identifier_form("bar")))); }), ((typeof _lisp_function_Ncompound_slice !== "undefined" ? _lisp_function_Ncompound_slice : lisp_undefined_identifier("%compound-slice", "function", undefined))(null, (typeof _lisp_variable_NNform !== "undefined" ? _lisp_variable_NNform : lisp_undefined_identifier("%%form", "variable", undefined)), (lisp_number("+1"))))))); }))) ]]

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)